NERVE INJURIES

How do we manage trigeminal nerve injuries?

Please see article by Renton & Yilmaz, 2012 on the management of iatrogenic trigeminal nerve injuries.

Current management of these nerve injuries is inadequate. There is only discussion on surgical correction and no attention to medical or counselling intervention. In part the fault rests with how we assess these patients and there is a deficiency in functional and pain evaluation and a total focus on basic mechanosensory evaluation which is not necessarily reflective of the patients’ difficulties. A recent review of publications pertaining to trigeminal nerve repair highlights that the average time from injury to nerve exploration was 16 months; this is far too late to prevent central neural changes due to altered peripheral input (neuropathic pain) (Ziccardi & Zuniga 2007).

Most importantly the clinician must establish the patients’ expectations. After a comprehensive assessment the possible timing of any necessary intervention may be indentified. The fundamental question is ‘What is the patient complaining of?’ It may be pain or discomfort, functional or social problems or the patient expectations of the treatment process. Normal sensation is unlikely to return to normal after 3-6 months with or without intervention. The patient also requires reassurance that the nerve injury will not increase risk of cancer or other pathology.

Update on trigeminal nerve repair

Overall, the evidence is poor and ideally all pts should have immediate repair latest few days with CBCT scanning you can detect breech of the lingual plate and Frederic and I have been involved in developing MR neurrography which may also play a role in early detection ID nerve injuries…. both allowing for earlier intervention.

Bagheri et al of 222 cases suggest 9 months max (Bagheri SC, Meyer RA, Khan HA, Kuhmichel A, Steed MB. Retrospective review of microsurgical repair of 222 lingual nerve injuries. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010 Apr;68(4):715-23. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.09.111. Epub 2009 Dec 29. PMID: 20036042.)

Effectivity of nerve repair

- age of patient Younger better FSF recovery [Fagin AP, Susarla SM, Donoff RB, Kaban LB, Dodson TB. What factors are associated with functional sensory recovery following lingual nerve repair? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012 Dec;70(12):2907-15. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2012.03.019. Epub 2012 Jun 12. PMID: 22695009.] and

- younger age of patient and technique (Kang SK, Almansoori AA, Chae YS, Kim B, Kim SM, Lee JH. Factors Affecting Functional Sensory Recovery After Inferior Alveolar Nerve Repair Using the Nerve Sliding Technique. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021 Aug;79(8):1794-1800. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2021.02.036. Epub 2021 Mar 1. PMID: 33781730.

- presence of neuropathic pain

- it is well published that neuropathic pain does not respond to surgery in general and more specifically trigeminal nerve injurieszuniga & Renton attached

- Zuniga JR, Yates DM. Factors Determining Outcome After Trigeminal Nerve Surgery for Neuropathic Pain. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016 Jul;74(7):1323-9. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2016.02.005. Epub 2016 Feb 18. PMID: 26970144.

- Zuniga JR, Yates DM, Phillips CL. The presence of neuropathic pain predicts postoperative neuropathic pain following trigeminal nerve repair. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014 Dec;72(12):2422-7. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2014.08.003. Epub 2014 Aug 11. PMID: 25308410.

- Bagheri SC, Meyer RA, Cho SH, Thoppay J, Khan HA, Steed MB. Microsurgical repair of the inferior alveolar nerve: success rate and factors that adversely affect outcome. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012 Aug;70(8):1978-90. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.08.030. Epub 2011 Dec 16. PMID: 22177818.

- Renton Egbuniwe Nerves and Nerve Injuries Vol 2: Pain, Treatment, Injury, Disease and Future Directions 2015, Pages 469-491

- Renton T Van der Cruyssen F Diagnosis, pathophysiology, management and future issues of trigeminal surgical nerve injuries November 2019 Oral Surgery 13(4)

- it is well published that neuropathic pain does not respond to surgery in general and more specifically trigeminal nerve injurieszuniga & Renton attached

- which nerve However, Simon Aitkins recently published a series of LNI patients from Sheffield showing positive results ( not explicitly pain relief) in patients undergoing LN repair ( all be it my pts referred t him did not improve!)

- Atkins S, Kyriakidou E. Clinical outcomes of lingual nerve repair. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021 Jan;59(1):39-45. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2020.07.005. Epub 2020 Aug 13. PMID: 32800402.

- Leung YY, Cheung LK. Longitudinal Treatment Outcomes of Microsurgical Treatment of Neurosensory Deficit after Lower Third Molar Surgery: A Prospective Case Series. PLoS One. 2016 Mar 4;11(3):e0150149. attached

- 29 cases presented by my PhD Student Frederic in Leuven

Managing post-traumatic trigeminal neuropathic pain. Is surgery enough?

Possible interventions and timing

The clinician must discern exactly what are he or she is trying to treat the patient for, is it poor mechanosensory function (continually the focus of many surgical studies) or more pertinently should it be what the patient is complaining of? The patient will often complain of;

- Disability associated with

- Altered sensation, severe discomfort, pain or numbness

- Large neuropathic area

- Interference with eating and drinking etc

- Can’t cope! Many patients find accepting or coping with even minimal iatrogenic nerve injuries very difficult. This may be due to the unexpected nature of the injury, poor informed consent, poor post operative management of the patient and lack of information.

The planned treatment must address the patients concerns appropriately and the aims of treatment would ideally provide;

- Improved function: Treatment will NOT restore function completely of eating, drinking, speaking, sleeping

To improve sensation

Treatment will NEVER restore normal sensation in:

- Neuropathic area

- General sensory (ie. mechano-sensory function)

- Special sensory (ie. taste)

To reduce pain or altered sensation

Escalating a patient from intermittent pain to persistent pain would be a negative outcome as would causing a patient to have discomfort or pain when previously they had only anaesthesia.

As previously highlighted the management will depend on the mechanism and the duration of the nerve injury. Many injuries have limited benefit from surgical intervention and should be managed symptomatically. URGENT treatment is indicated in endodontic and implant related nerve injuries

Implant injury

These injuries may be irreversible and place the emphasis on prevention rather than cure.

- Planning >4mm safety zone

- Bleed during implant bed preparation – delay implant placement

- Persistent numbness after LA has worn off – remove implant < 36 hours

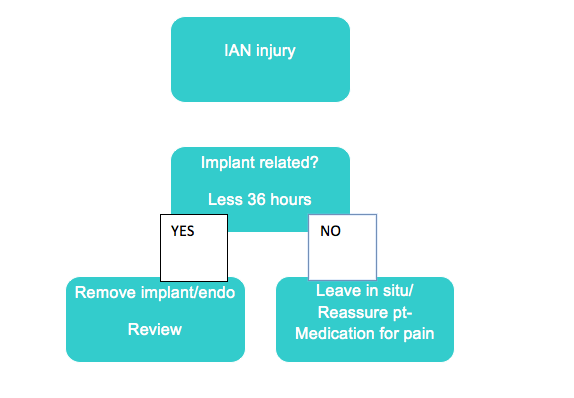

Management of implant related nerve injuries

IAN injury

Endodontic (root canal) related nerve injury

Based on the current evidence the authors would recommend the practitioner undertaking the endodontic care

Preoperatively should identify teeth proximal to the IAN and take special care in preventing apical breech.

Intraoperatively would recognise and record certain events during treatment including:

- Intraoperative pain during irrigation

- Intraoperative pain during preparation and filling

- Inferior alveolar vessel bleed during preparation and delay filling

Postoperatively if endodontic nerve injury is suspected the post operative radiograph must be scrutinised for evidence of breach of apex and deposition of endodontic material into the IAN canal. If this is suspected the material, apex and or tooth must be removed within 48 hours of placement in order to maximise recovery from nerve injury.

Routinely contact patients post operatively to ensure local analgesia has worn off. If nerve injury occurs or is suspected after the procedure, the clinician must inform the patient of its existence immediately and consider removing the overfill of endodontic material, or apicect or extract tooth if present in less than 30-48 hours

If however there is no evidence of overfill resent may be

- apical inflammation (neuritis) confirmed by prescription of antibiotics

- chemical nerve injury from irrigant or endo material

- thermal damage

In any event once neuropathy is identified the clinician must reassure the patient prescribe steroids (Prednisolone step down 15mg 5 days, 10mg 5 days and 5mg 5days and high dose NSAIDs, 600mg Ibuprofen) and make a timely referral to an appropriately trained micro neurosurgeon if necessary.

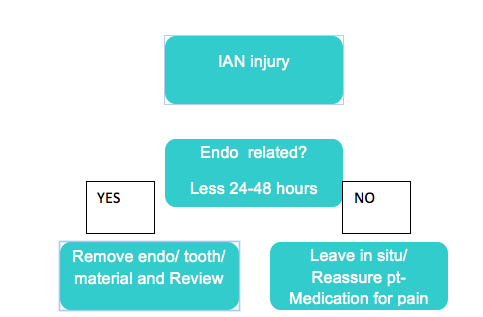

IAN injury

Nerves damaged by local anaesthetic remain grossly intact and surgery is not appropriate as one cannot identify the injured region.

You may be at increased risk of nerve injury

- If you experience pain on injection during treatment

- If you have multiple deep injections

- Or a high concentration anaesthetic agent (Articaine, Prilocaine, Mepivicaine) is used for deep injections (check with your dentist)

Some hints for the patient (see the following paper: BDJ LA nerve injury paper)

- Great care must be taken when selecting your clinician (avoid non specialists for complicated treatments and if you are in doubt contact the general dental council. We also suggest caution in seeking ‘cheap’ implant treatment abroad!).

- Many clinicians are using a low risk injection technique wherebye they give infiltrations (non deep injections next to the tooth) rather than deep block injections using higher concentration or normal agents in order to avoid uncessary deep injections.

- Ask your clinician as this is not always possible

- If you need a deep injection, avoidance of high concentration agents for deep block injections is recommended

- There isn’t much we can do with these nerve injuries aside for sitting and waiting for their recovery which may or may not happen. But we can see and advise the patients to reassure them

Recovery is reported to take place at 8 weeks for 85-94% of cases (Smith and Lung 2006). IAN injuries may have a better prognosis than lingual nerve injuries and if the duration of nerve injury is greater than 8 weeks then permanency is a risk. The problem with these injuries is that the nerve will remain grossly intact and surgery is not appropriate as one cannot identify the injured region. The management indicated is for pain management if the patient has chronic neuropathic pain.

Prevention of LA nerve injuries is possible. It has become routine practice for paedodontic extraction of premolars using infiltrations and many practitioners are routinely undertaking restorative treatment of premolars and molars in adults using LA infiltrations rather than inferior alveolar nerve blocks. This reduces the incidence of these troublesome untreatable injuries.

Simple steps to minimise LA related injuries

- Avoid multiple blocks where possible

- Avoid IAN blocks by using Articaine infiltrations only

- Avoid high concentration LA for ID blocks (use 2% Lidocaine as standard)

Intra-operatively all clinicians should document unusual patient reactions occurring during application of local analgesic blocks (such as sharp pain or an electrical shock–like sensation).

Possible management tools for permanent nerve injuries

- Counselling is indicated for all patients with nerve injuries caused by;

- Endo > 24-48 hours

- Implant > 24-48 hours

- Wisdom teeth > 3-6months

- LA > 3-6 months

- Orthognathic > 3-6months

- Fracture > 3-6months

- Medical symptomatic therapy is indicated for patients with pain or discomfort and for patients with anxiety and or depression in relation with chronic pain.

- Topical agents for pain

- Systemic agents for pain

- Surgical exploration

- Immediate repair if nerve section is known

- Remove implant or endo material within 24 hours

- Explore IAN injuries thro socket less than 4 weeks

- Explore LN injuries before 12 weeks

Reassurance counselling / Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

The clinician must consult the patient in depth, reaffirm the nerve injury is permanent and provide reassurance and explanation. Often patients who can manage their pain but have associated functional difficulties are successfully managed by an explanation of their symptoms and informed of the permanency of their condition with realistic expectations. They can also be reassured that these injuries do not predispose them to cancer and indeed will never worsen.

Increasingly there is evidence for successful treatment of chronic conditions using Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT). Within our field chronic temporo-mandibular pain conditions can be successfully treated and CBT or formal counselling may have an increasing role particularly for patients with injuries who are unable to cope with the consequences of their nerve injury which may be significantly impacting their social or work ability. To date there is no evidence for the assessment of counselling treatment for IANIs or LNIs.

Medical intervention

Since the altered sensation may be due to an inflammatory reaction, a course of steroid treatment may minimise inflammation and reduce damage to the nerve (oral Prednisolone 1mg per Kg per day – maximum 80mg) for first week with stepping down 10mg daily over the following week. This is combined with a high dose of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication (such as ibuprofen, 800 milligrams, three times per day) which should be prescribed for three weeks. There is minimal evidence base for steroid medication for the prevention of peripheral sensory nerve injuries (Von Arx 1989) however it is routinely prescribed for Bell’s palsy and viral infections of the facial nerve.

The majority of patients presenting with neuropathic pain require analgesia. Routine analgesics do not work for chronic neuropathic pain and in effect these patients are best treated with topical or systemic medications generally used for other chronic pain conditions.

The first line medication for neuropathic pain is either TCAs (amitriptyline or nortriptyline) or antieplieptics (carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, pregabalin or gapapentin). In two cases the patient continued their medication to control their neuropathic pain. 6 other patients had tried these medications beforehand and could not tolerate the side effects. As an alternative many patients seen with extraoral IAN neuropathy with mechanical allodynia interfering with function are offered to try 5% Lidocaine topical patches (Khawaja and Renton 2009). To date there is no evidence for the treatment of IANIs or LNIs using any form of medication.

Cognitive behavioral therapy is being developed within the department for patients with IANIs however none of these patients were offered this treatment.

Surgical intervention

Surgical intervention for repair of iatrogenic trigeminal nerve injury has remained the focus for our specialty. Being of mechanistic temperament we have focused on the technical aspects of surgery rather than a holistic perspective. A metanalysis of surgical intervention for trigeminal nerve injuries is not possible as there are no prospective randomised studies in this field.

A review of 26 studies reporting lingual nerve repair highlights the variation in reported patient, management and surgical parameters. Only two studies identify selection criteria for surgical repair and the mean delay from injury to repair is over 16 months.

Surgical findings will dictate the surgical intervention for these nerve injuries

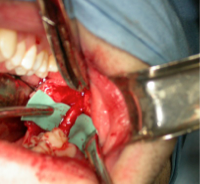

1. ‘Normal nerve’ Exploration. On surgical exploration if the nerve is apparently uninjured then no surgical alteration of the nerve is indicated (figure 16).

Figure On exploration the lingual nerve appears to be uninjured

2. Release scarring over ‘normal nerve’ Decompression. If on release and dissection of scar tissue in the region the nerve is uninjured on exposure again there is no indication for surgical alteration of the nerve. However, the release of surrounding scar tissue (external neurolysis or surgical decompression Figure 17) has been reported to provide improvement for patients with IANIs and LNIs.

Figure On exposure and removal of scar tissue around the lingual nerve the nerve appears intact.

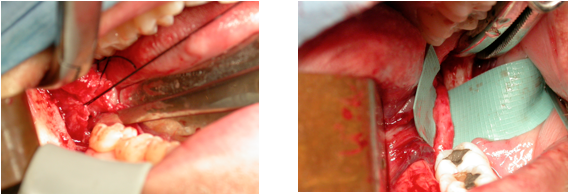

3. Nerve interrupted by scar tissue or neuroma. If on exposure of the nerve scar tissue or neuroma formation is found to interrupt the continuity of the nerve (Neuroma in continuity [NIC] Figure 18) excision of the neuroma or scar tissue and re-approximation of the ‘fresh’ nerve endings is indicated. This is performed under surgical microscopy or high magnification loupes. Anastimosis using epi-neural sutures (usually 4-8 using 6/0-8/0 either vicryl or nylon sutures) is recommended with minimal tension otherwise the tension itself may precipitate neuropathic pain. If the inter-neural space is large some authors recommend grafting (using Sural nerve); however, outcomes form grafting are poor and this is now rarely indicated. If approximation requires too much tension then the space is left and not grafted, this also avoids complications arising from the nerve graft site.

Figure Exploration reveals the lingual nerve to be interrupted by scar tissue / neuroma which on excision allows for re anastimosis of the nerve.

4. Nerve completely sectioned. If on exposure of the nerve it is found to be completely sectioned with end neuromata (EN) formation, excision of damaged endings followed by re-approximation of the ‘fresh nerve endings’ is recommended. If the gap is too large to allow anastimosis with tension then a gap is left. This more commonly occurs with IANIs due to difficulty with mobilisation within the ID canal. Even with extensive buccal corticotomy closure of gaps approaching 2cm are difficult without tension.

Surgical approach for IAN (lip nerve) injuries will vary but the principles of findings on surgical exploration dictating the applied technique remains similar

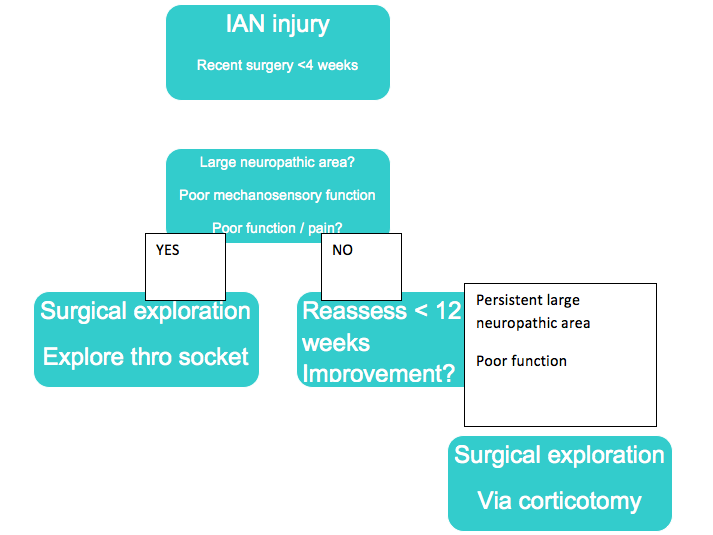

Figure Suggested algorithm for management of IANIs

IAN injury

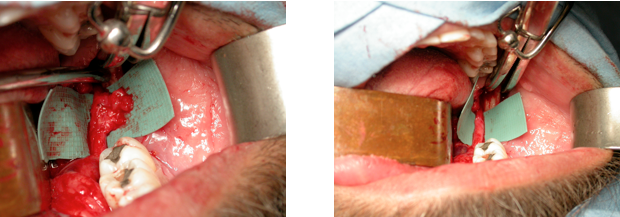

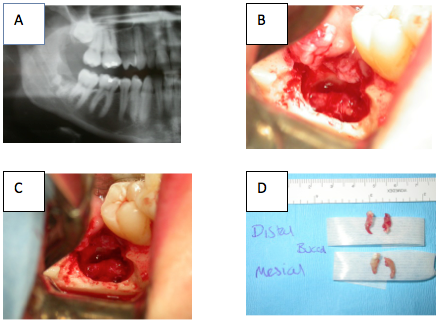

1. Exploration of the IAN via the socket. If the IANI is less than 6-8 weeks then assess using a pre operative radiograph for retained roots and obvious compression of the canal. If the injury presents early on the IAN can be explored via the socket (Figure 20)

Figure A Illustrates retained roots associated with severe IAN nerve injury at 3 weeks. B exposure of IAN via socket. C appearance of IAN on removal of roots and debris. D Picture showing both roots of lower left 8 after removal were perforated by IAN.

The attempted extraction took over 3 hours; the patient was suffering from extreme neuropathic pain and 100% neuropathy.

The exploration took place at 4 weeks with the roots removed both circumscribing the IAN. The patient made a complete recovery at 8 weeks post extraction.

2 If the IANI is of longer duration with a healed socket the preferred surgical approach may be using a lateral corticotomy (Figure 21). Some authors have recommended full lateral corticotomy with the removal of buccal plate from lower 8 region to mental foramen to facilitate mobilisation of the IAN. However very few reports using this method suggest improved outcomes.

Figure Intra-operative picture illustrating lateral corticotomy and exposure or IAN which may or may not require surgical modification.